| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |

| As there are far too many pages of this type, this page must be edited to be original at the earliest possible moment. |

| This tag must not be removed until the rewrite is done — doing so is a (possibly criminal) violation of Wikipedia's copyright. |

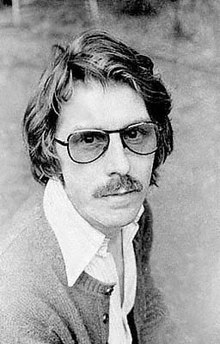

Derek Taylor (7 May 1932 – 8 September 1997)[1] was an English journalist, writer and publicist, best known for his work as press officer for the Beatles. He started his career as a local journalist in Liverpool aged 17 working for the Hoylake and West Kirby Advertiser followed by the Liverpool Daily Post and Echo[2] before becoming a North England-based writer for national British newspapers that included the News Chronicle, the Sunday Dispatch and the Sunday Express. He also served as a regular columnist and theatre critic for the Daily Express from 1952.[3]

A trusted confidant of the Beatles, Taylor remained particularly close to George Harrison and John Lennon long after the band's break-up. In addition to working as editor on Harrison's 1980 autobiography, I, Me, Mine, Taylor authored books such as As Time Goes By, The Making of Raiders of The Lost Ark, Fifty Years Adrift (In An Open Necked Shirt) and It Was Twenty Years Ago Today.

Work with the Beatles[]

Derek Taylor was a national journalist working for the Daily Express when he was assigned to write a review of a Beatles concert on 30 May 1963. He had been expected by his editors to write a piece critical of what at that time was considered by the national press as an inconsequential teen fad. However, he was enchanted by the group and instead sang their praises. Shortly afterwards, he was invited to meet the Beatles and soon became a trusted journalist in their circle.

As the band gained national attention in Britain, Taylor's editors conceived of running a column ostensibly written by a Beatle to boost circulation, to be ghostwritten by Taylor. George Harrison was the Beatle eventually decided upon. Although Taylor was initially only given the right to approve or disapprove of the content, Harrison's dissection of the first draft turned the column into an ongoing collaboration between the two, with Harrison providing the stories and Taylor providing the polish.

In early 1964, Beatles manager Brian Epstein hired Taylor away from his newspaper job, putting him in charge of Beatles press releases, and acting as media liaison for himself and the group. He subsequently became Epstein's personal assistant for a short period. In mid-1964 Taylor assisted Epstein in the writing of Epstein's autobiography, A Cellarful of Noise. Taylor conducted interviews with Epstein for the book and then shaped the transcriptions of the audio recordings into a narrative, retaining most of Epstein's basic words.

Taylor served as press officer for the Beatles' first concert tour of the US in the summer of 1964, resigning from his position at the end of the tour in September. Brian Epstein demanded however that Taylor continue working for a three month notice period. After this he went to work for the Daily Mirror. Taylor then left the UK and moved with his growing family to California in 1965 where he started his own public relations company, providing publicity for groups such as the Byrds, the Beach Boys and Paul Revere and the Raiders. Among Taylor's skilful strategies was the positioning of the Byrds as being a new breed of American band with parallels to the Beatles, as well as encouraging nascent rock writers to perceive Beach Boys founder Brian Wilson as a musical genius. Taylor was a key participant in the team that produced the historic Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, serving as its publicist and spokesman.[4]

George Harrison's song "Blue Jay Way" was written during Harrison's 1967 visit to California, on a foggy night waiting for Taylor and his wife to come visit ("There's a fog upon L.A./And my friends have lost their way"). Finding a small electric organ in his rented house (on Blue Jay Way), Harrison worked on the song until they arrived. Taylor also accompanied Harrison on his trip to the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco.

Taylor was also a catalyst in Harry Nilsson's musical career; hearing Nilsson's song "1941" on a car radio, he bought a case (twenty-five copies) of his album Pandemonium Shadow Show, sending copies to various music-industry contacts. Among the recipients were all four Beatles, who became enamoured of his talent and invited Nilsson to London. Nilsson subsequently became a collaborator and good friend of both John Lennon and Ringo Starr.

In April 1968, at Harrison's request, Taylor returned to England to work for the Beatles again, as the press officer for their newly created Apple Corps.[5] As a key executive at Apple, Taylor had a major role in the company's activities, involved in many of the key projects of the Beatles and Apple. His prominent role is documented in The Longest Cocktail Party, a memoir of Apple in the late 1960s by Taylor's junior assistant (dubbed the Apple "house hippie") Richard DiLello, and in other Beatles biographies. During March 1970, Taylor commissioned the young photographer Les Smithers to photograph Badfinger, a rock band that Apple Corps had assigned to its new record label. That portrait has now been acquired by the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Among Taylor's projects for Apple, he played a significant part in the staging of John Lennon and Yoko Ono's 1969 campaign for world peace. Taylor was referenced in the lyrics of Lennon's song "Give Peace a Chance", along with Tommy Smothers, Timothy Leary and Norman Mailer, who like Taylor were all present at the recording of the song.

After the Beatles[]

After he left Apple in 1970 following Allen Klein's restructure of the organisation, Taylor went to work for the newly launched UK record company Warner Music Group, the British umbrella company that distributed and marketed several labels owned in the US by the Kinney Corporation. These labels included Warner Bros, Reprise, Elektra and Atlantic Records. Taylor served as Director of Special Projects, working with artistes such as the Rolling Stones, Yes, America, Neil Young, Vivian Stanshall, Carly Simon and Alice Cooper. He also presided over a revival of British jazz singer George Melly, producing two albums for him. He was instrumental in signing seminal Liverpool Art School rock band Deaf School, featuring future record producer Clive Langer.

Independently of his work for Warner Music Group, Taylor co-produced Nilsson's A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night in 1973. He had previously provided liner notes for Nilsson's Aerial Ballet album. (A story written by Taylor's daughter Victoria was printed on the back cover of Nilsson's album Harry.)

Return to America[]

In the mid-1970s he served as a Vice-President of Marketing for Warner Bros. Records, where he was instrumental in the acquisition of the Rutles project, and supervised the worldwide marketing campaign for the album release and TV special. A spoof on the Beatles' career and legacy, the Rutles' All You Need Is Cash TV special featured Harrison playing a Derek Taylor-like character. Taylor left Warner in 1978. As well as staying close to Harrison throughout the 1970s, Taylor maintained a correspondence with Lennon during the latter's years of retirement between 1975 and 1980. Taylor did not enjoy his second period in California, however, and returned to England after a couple of years.

Back in England[]

In the early 1980s he worked as a co-author on books with Michelle Phillips and Steven Spielberg. He also worked with George Harrison's film company, Handmade Films. In the early 1990s he was asked to rejoin Apple to be in charge of marketing of the multiple projects planned for that decade, which included the CD release of the original Apple catalogue and major Beatles releases such as Live at the BBC and compilation albums associated with The Beatles Anthology.

Work as an author[]

In 1973 he wrote a very informal memoir, As Time Goes By, published by Sphere Books and reprinted by its Abacus imprint the following year.

Over 1978–79, Taylor collaborated again with Harrison, helping him to complete his autobiography, I Me Mine, published in 1980 by Genesis Publications. The following year, Taylor's on-set account of the production of Raiders of the Lost Ark was published as The Making of Raiders of The Lost Ark by Ballantine Books. He subsequently wrote his own autobiography, Fifty Years Adrift (In An Open Necked Shirt), published in December 1983 by Genesis, for which Harrison provided a glowing introduction to the signed, limited-edition volume. Only 2000 copies were printed, and the book quickly became a collectors' item after Harrison joined Taylor in promoting the publication.

In 1987, Taylor's It Was Twenty Years Ago Today (published by Fireside for Simon & Schuster) celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the release of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, providing a detailed documentary of the people and events that shaped the album and the wider events of the Summer of Love counterculture. The book includes archive interviews and photographs as well as extensive transcripts from a Granada TV documentary instigated by Taylor, also titled It Was Twenty Years Ago Today.

As Time Goes By: Living in the Sixties (Rock and Roll Remembrances Series No 3) (Popular Culture Ink) was published in June 1990 in the US, while in the UK Bois Books published What You Cannot Finish and Take A Sad Song in 1995, coinciding with the release of The Beatles Anthology (Taylor was extensively interviewed for the TV program). Posthumous volumes include Beatles (Ebury Press 1999). In addition, an audio CD, Here There and Everywhere: Derek Taylor Interviews The Beatles, was released on the Thunderbolt label in 2001.

Death[]

Derek Taylor died of cancer on 8 September 1997 at the age of 65. At the time of his death he was still working for Apple, helping to compile the Beatles Anthology book. His funeral took place in London, attended by family and friends such as Harrison, Neil Aspinall, Neil Innes, Michael Palin and Jools Holland.[6]

Personal life[]

Taylor was married to Joan Taylor (née Doughty) from 1958 until his death. The couple had six children: Timothy, Dominic, Gerard, Abigail, Vanessa and Annabel.[7] Joan Taylor appeared in his stead in the documentary George Harrison: Living in the Material World.

References[]

- ↑ "Obituary: Derek Taylor". The Independent . http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-derek-taylor-1238372.html.

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-derek-taylor-1238372.html,

- ↑ "Obituary: Derek Taylor". The Independent . http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-derek-taylor-1238372.html.

- ↑ "Obituary: Derek Taylor". The Independent . http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-derek-taylor-1238372.html.

- ↑ Johnny Black, "A Slice of History", Mojo: The Beatles' Final Years Special Edition, Emap (London, 2003), p. 89.

- ↑ Keith Badman, The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001, Omnibus Press (London, 2001; ISBN 0-7119-8307-0), p. 575.

- ↑ Obit

External links[]

- Philm Freax original photos

- Official Apple Obituary

- It Was Twenty Years Ago Today (Granada documentary)

- A tribute to Derek Taylor

- Badfinger portrait in National Portrait Gallery.